Detroit’s ‘Personal Luxury’ revolution defined the American car, at home and across the globe, for a generation, says BK Nakadashi. Kicking off our Personal Luxury Special, BK forensically examines the rise and fall of this uniquely American genre of motor car…

For decades, luxury and power have gone hand in hand. You’ll recall that the OHV V8 revolution began at Cadillac and Oldsmobile, GM’s ritziest divisions, for the 1949 model year and in 1951, Chrysler had the 331-cube Hemi at the top of its food chain.

But by 1955, OHV power had filtered down to the more plebian divisions (ie Chevy, Ford and Plymouth), and power was available in any class of car. This meant that the luxury cars needed a little something extra.

Enjoy more Classic American reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The new Chrysler 300 had the power and all of the American luxury-car trappings you’d want – electric-powered everything, automatic transmission, the works. But the 300 was too large to be considered ‘personal’. That same year, Ford’s two-seat Thunderbird announced the “personal-luxury” concept in its ads.

It was a surprise hit, but in order to survive, Ford determined that it needed to grow: in power, in options and toys, and in the number of seats. This second-generation Thunderbird, arriving early in calendar 1958, is ground zero for the American personal-luxury car (see our exclusive feature on the development of that seminal car starting on page 52).

That same year, you could buy a 400bhp production automobile out of an American showroom – a Mercury, for the record. Luxurious? Probably. But personal-luxury? No. Only Thunderbird touted that.

The concept was refined and slowly expanded throughout the Sixties. Much like OHV V8 power, personal-luxury machines started in the higher-ranked divisions of the Big Three, and filtered their way down through the ensuing decade. Studebaker’s Raymond Loewy-penned Avanti 2+2 coupe was a terrific idea that so took Studebaker by surprise that they couldn’t build it quickly enough.

Buick ended up with the Riviera for 1963, largely because Cadillac turned it down; it was a greater marketing-and-image success than a sales victory. Even so, Cadillac kicked itself and quickly began the development of a personal-luxury coupe that borrowed technical underpinnings from one that Oldsmobile was working on.

The front-wheel-drive Olds Toronado arrived for ’66, and because Cadillac was late to the party, and in deference to Olds spearheading the project, the front-drive Eldorado appeared a year later. Mercury’s Cougar split the difference between the Mustang and the Thunderbird, in size and cost; whilst Lincoln’s Mark III coupe arrived in 1969.

And it was 1969 when things really started rocking for the personal-luxury-car movement. Beyond Lincoln’s efforts, GM launched a one-two personal-luxury punch (in a velvet glove?) with the ’69 Pontiac Grand Prix and, more crucially, the 1970 Chevy Monte Carlo.

Both rode the new “A-Special” 116-inch chassis that saw a standard coupe chassis with the front wheels pushed forward four inches; the effect was a cabin that rivalled other A-body coupes, but with more dramatic long-nose proportions. Additional inches ahead of the front suspension made hoods and fenders seem grander still.

The start of the Seventies saw the genre continue on down the food chain. Dodge’s Charger offered an SE package that was more mush than muscle, and Ford introduced the formal-roofed Mustang Grande as a sort of junior Thunderbird.

Full-size car grandiosity in a mid-size body was the extension of a trick that Detroit learned with muscle cars: with the right gingerbread and marketing, smaller cars need not be loss-leaders after all. A compact or mid-size could cost as much as a full-size to develop, but had to sell for less because of its size; muscle cars proved that mid-sized cars could be just as profitable.

And so, at the start of the Seventies, when the psychedelic spectacle of high-performance evaporated from American dealer forecourts, and the concepts of luxury and power were no longer intertwined, there was suddenly a big fat money hole in Detroit’s pockets. Detroit had weaned itself on big money from smaller cars, but when the performance went away, so did profits. Something had to take its place.

This is when the personal-luxury car, waiting in the wings for all those years, was finally allowed to strut forth and take its place in the spotlight. The answers from all of the car companies were inevitably similar: with power removed from the equation, Detroit loaded in the toys and the high-style faux-wood and chrome filigree.

When new V8s were choked down to power figures like the old Sixes had, Detroit simply slotted in bigger engines – usually backed with automatic transmissions, so that you could float off on a wave of torque from a stop light. Four-cylinder cars got sixes… and occasionally a V8 too.

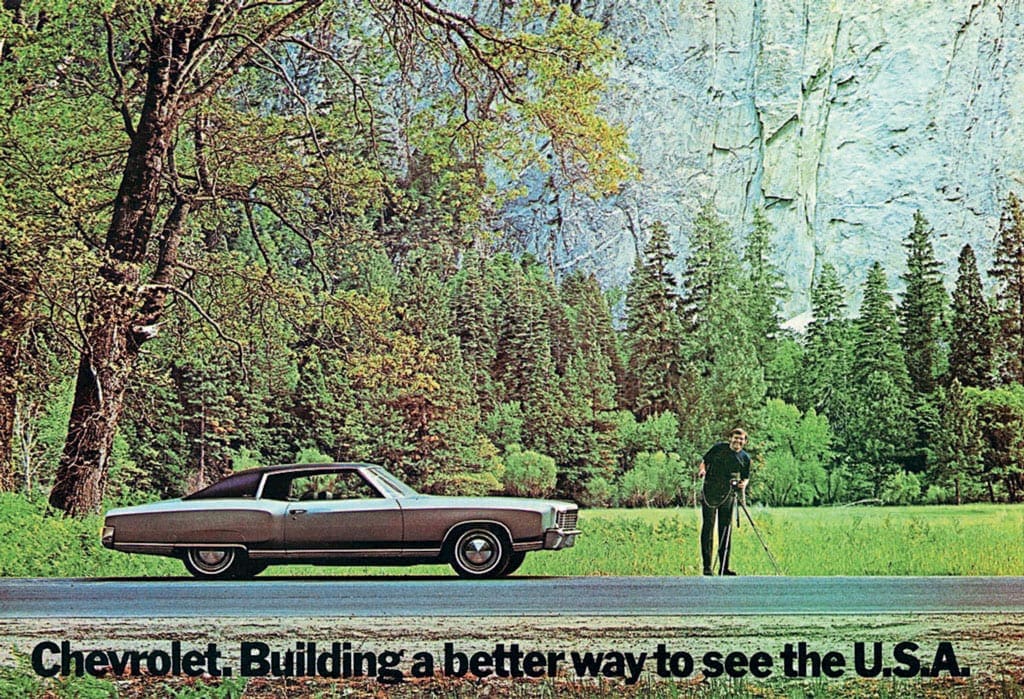

The personal-luxury movement arrived at (arguably) exactly the right moment in American history. Nearly 200 years of independence, and behind all of the flag waving and tricolour bunting, the future – indeed the world at large – scared the beJesus out of most Americans.

Viet Nam, Watergate, the civil rights movement, the social upheavals of the Sixties… things had changed quickly, and the nation needed a calming influence. Muscle cars were hard cars for hard times; in the Seventies, cars again reflected and predicted the American driver’s needs.

The personal-luxury car is all about being shrouded from the jarring reality of the outside world; passengers are an unwelcome intrusion (as the size of the back seats fairly announce to anyone paying attention). Why shouldn’t our cars symbolically protect us from the horrors of everyday life? Hadn’t we been through enough already?

And so: Mile-long hoods; stand-up hood ornaments; acres of chrome, velour, and fake wood; Andrex-soft interior; colour-co-ordinated everything, to soothe our eyes; paint palates of muted earth tones and rich, deep hues; vinyl tops; tinted rear glass area, lest anyone outside be able to see in; four-speaker stereos whispered Muzak or the Carpenters; super-soft suspensions and white-wall radial tires; single-finger power steering; and acres of sound insulation deadened anything that the outside world may have thrown a driver’s way.

Outside, bright and colour-keyed trim ruled the day – additional moldings (with colour-keyed trim inserts), a special badge, full wheel covers (that were occasionally colour-keyed to the body, if they weren’t faux-wires), two-tone paint, remote door mirror(s).

Inside, stereos that offered your choice of cassette or eight-track tape (along with AM, FM and, in some cases, CB radio!) and power- steering/brakes/windows/locks. Inside, the steering wheel, steering column, seats, door panels, carpets, seatbelts and headliner, were a monochromatic wash of colour.

Multi-adjustable seats (sometimes power-operated) were clad in the softest of fabrics. Air conditioning blew cool when the temperature of the world’s political rhetoric got too hot. Cars became cocoons – our safe spaces, our sensory deprivation tanks. Personal-luxury models were the epitome of this – at a popular price.

The technology wasn’t new; lots of it had been in cars for decades. What was new was bringing it down the line into smaller cars, and charging a premium for it. And it worked. Sales of intermediate-sized cars had been steady throughout the Sixties, roughly 20% of total sales of a given division.

In 1972, intermediates suddenly took the lead. Seventy-five percent of these were two-doors, and half of those were personal-luxury models. From 200,000 cars in 1970, sales topped one million in ’75. Big, soft, distant – fuel crisis or not, these were the right cars at the right time.

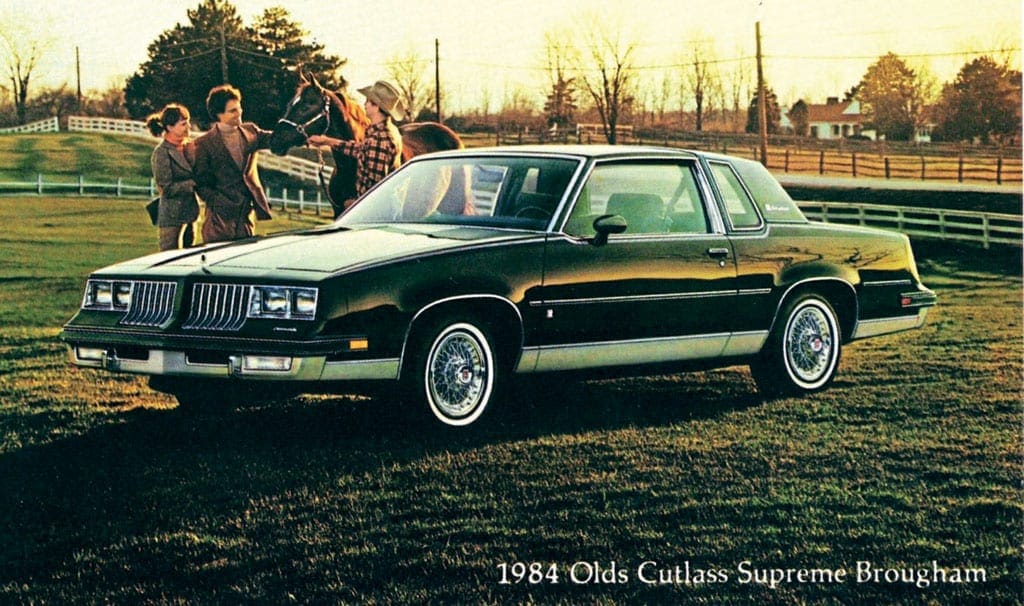

If we were to pick a point where the personal-luxury era really kicked off, it would be the fall of ’72, with the launch of GM’s redesigned “A-Special” chassis cars: Monte Carlo and Grand Prix led the brigade, joined now by formal-roofed versions of the two-door Olds Cutlass (called Cutlass Supreme) and Buick Century (called Century Regal).

The General went all in on personal-luxury for 1973. And the sales numbers were impressive: 290,000 Monte Carlos, nearly 154,000 Grands Prix; 219,000 Olds Cutlass Supreme two-doors; and more than 91,000 Buick Century Regals. Plus, because these mid-sized coupes were smaller than traditional big cars, they were perfectly placed to blow up bigger still once the first chapter of the OPEC oil crisis had played out. All the same toys as a Cadillac or Lincoln… in a smaller size. America went bananas, and it was all Detroit could do to keep up.

For 1974, Mercury kicked the Cougar upmarket and away from the Mustang. The new-for-’75 Chrysler Cordoba was the “small” car that management once swore it would never build; Cordoba production accounted for half of Chrysler’s sales for a couple of years in the Seventies, arguably saving Chrysler from bankruptcy (or at the very least, delaying it).

By 1975, you couldn’t avoid cars loaded with colour-co-ordinated seat belts and shag carpeting. The luxury-compact wave of ’75 (Ford Granada, Chevy Nova Concours, Cadillac Seville, Dodge Dart SE) brought all of the luxury trappings the Big Three could muster to a smaller, still-more-efficient platform.

Few would think of these as personal-luxury cars today, despite their size: in those days, most were still sedans – and the bulk of personal-luxury models were coupes. You could go still smaller, and you could option a $3000 Ford Pinto with another $2000 worth of engine, transmission, air conditioning and special-feature groups.

Five grand could buy you a new LTD in those days. No one would dare suggest, in a world of Cordobas and Cutlasses, that a Pinto could be considered representative of the genre, but it tells you how the personal-luxury vibe spread throughout Detroit. Every division of every car company in America sold a car that could be considered a personal-luxury car. Even lowly AMC offered a Matador Coupe Brougham, with an optional interior designed by fashion designer Oleg Cassini.

And because every car company had a hand in decking out multiple models in finery and filigree, Detroit sold lots more personal-luxury cars than muscle cars. For example, Monte Carlo sales improved year-to-year from 1973-1977: 1.56 million total built in just five years, with a staggering 411,000 built in 1977. The best-selling Thunderbirds ever were built from 1977-79: more than 955,000 sold for the downsized seventh-generation Thunderbird.

The luxury-car-for-the-masses experiment was a success – but a short-lived one. Their time passed quickly: the Iranian revolution and the subsequent second oil crisis in 1979 upended the natural order of things in Detroit, and suddenly the most popular personal-luxury cars of the decade were shunned for their wasteful inefficiency.

Luxury coupes remained, of course: Buick’s Riviera and Cadillac’s Eldorado both survived the turn of the millennium. But they weren’t the force that they once were. Today’s small car comes with air conditioning, power windows, back-up cameras and stereos that would blow a Seventies home hi-fi unit out of the water. What does a larger car get you anymore, besides a bigger footprint and more power? The cosseting, the luxury and the toys are available up and down the line.

A personal-luxury car doesn’t make a lot of sense today, but they kept the American car industry alive in the Seventies just when Detroit needed it most.