Words: Huw Evans Photography: General Motors & FCA

One of GM’s most advanced manufacturing facilities is closing its doors. Our man in America Huw Evans looks at the reasons for this unfortunate decision in an era when Trump’s “Make America Great Again” ethos was meant to be bringing manufacturing jobs back to the US…

On November 26 last year, General Motors CEO Mary Barra announced that the controversial Detroit-Hamtramck assembly plant would have no products allocated beyond 2019. The decision to shutter the 4.1 million sq ft facility, located at 2500 East Grand Boulevard in Detroit, was met with predictable outrage by local workers, residents and politicians.

Detroit-Hamtramck, which currently builds the Buick LaCrosse, Chevy Volt, Chevy Impala and Cadillac CT6, is one of GM’s most advanced vehicle manufacturing facilities and one of only a few that can handle different vehicles on the same assembly lines.

Enjoy more Classic American reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Yet, with no profitable SUVs or trucks on its assembly lines and production down to one shift, (after a second was eliminated in December 2016 with the loss of 1270 jobs), it would seem that Detroit-Hamtramck, known in GM parlance as D-HAM, would be a clear target for closure. And once the lines do fall silent, the remaining 1348 hourly workers and 194 salaried employees will have to find new jobs.

Proud tradition

However, displacement and heartbreak are nothing new to this part of Detroit. Back in 1981, it was promised that the gleaming new, state-of-the-art GM facility would bring prosperity and stability to a city that was already in the throes of economic decline due to a shrinking tax base, a loss of manufacturing, and flight by residents from older inner-city neighbourhoods to the suburbs.

The Detroit–Hamtramck area where the plant is situated (it actually straddles the cities of Detroit and Hamtramck) was once a thriving, tight-knit community − one that provided hope and prosperity to generations of people and families − including waves of European, Afro-Caribbean and Asian immigrants.

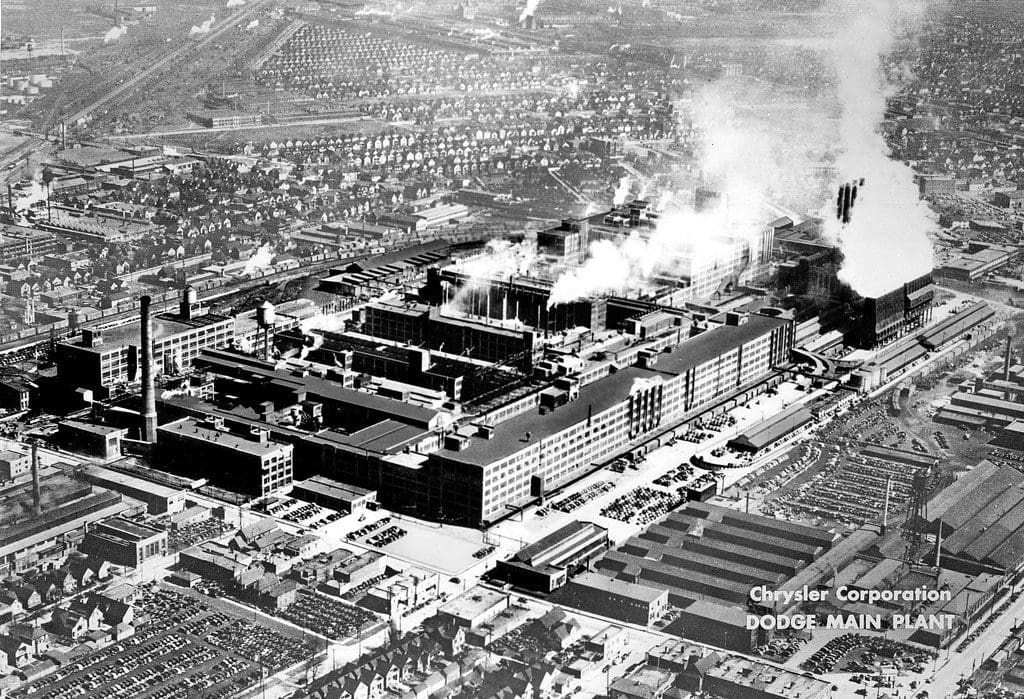

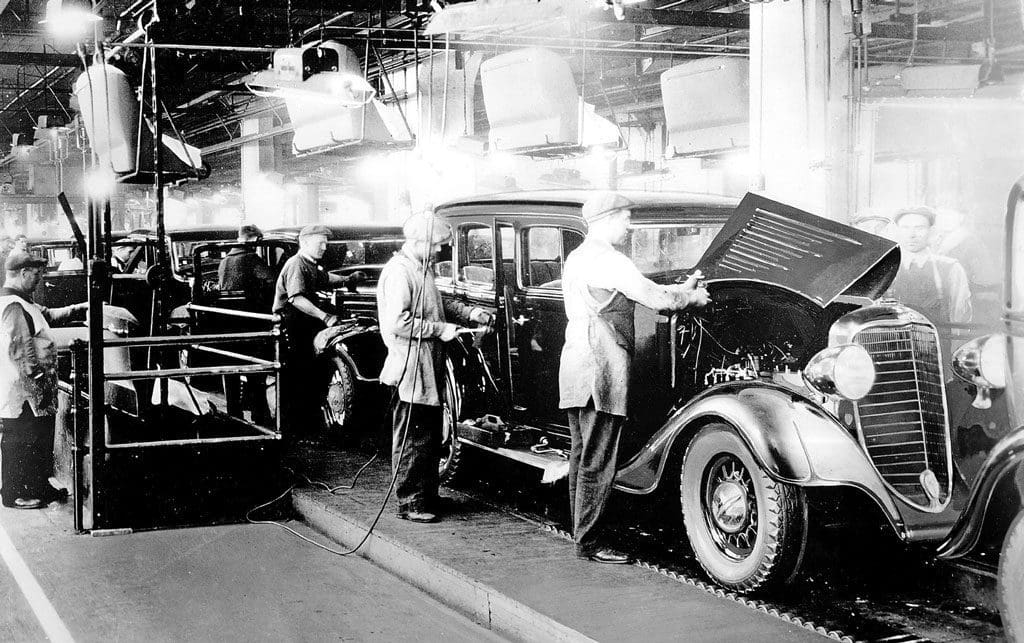

From 1911 until 1980, the area’s key economic hub was the Dodge Hamtramck assembly plant, colloquially known as Dodge Main. This multi-level facility, conceived by John and Horace Dodge and designed by Albert Kahn, dominated the local landscape and employed thousands of people.

During its peak years in the mid-Forties, Dodge Main boasted around 35,000 employees and at maximum capacity could assemble around 500,000 vehicles annually. It was an integral part of America’s Arsenal of Democracy during the war years. Dodge Main, which covered more than 100 acres, featured an on-site foundry and fire station, a fully-staffed medical centre, an expansive cafeteria and even an executive dining room − features which few assembly plants offered at the time.

Nevertheless, despite all of this, by the Sixties, Dodge Main was becoming increasingly antiquated. The multi-level assembly process was making the facility inefficient and costly to run, compared with newer and cheaper out of town assembly plants.

Working conditions also harked back to a bygone age and with Chrysler’s growing financial woes and quality control issues in the Seventies, coupled with production of vehicles like the tough-to-sell Dodge Charger, Coronet/Monaco and Aspen, Dodge Main was clearly on borrowed time.

It closed in January 1980; the last car rolling out the door being a 1980 Dodge Aspen R/T purchased by an electrical contractor named Robert Nellis. A year later, Dodge Main had been all but razed to the ground.

Rising from the rubble

The site on which GM proposed to build its new facility encompassed some 362 acres which not only included where the old Dodge Main plant once stood, but the residential districts to the north, representing some 1400 homes, 140 businesses and several houses of worship, including the Church of Immaculate Conception.

The decision to acquire the residential area, through the power of eminent domain (where government can effectively seize private land for public use by providing fair compensation to residents) was highly controversial and led to complaints which went all the way to the Michigan Supreme Court.

In spite of all this, as well as fervent objections led by local priest Joseph Karasiewicz and a groundswell movement of public protest − culminating in a sit-in at the Church of Immaculate Conception − the fight against the building of Detroit-Hamtramck ultimately came to naught.

Detroit Mayor Coleman Young and even the local Archdiocese pledged their support for building the new GM assembly plant, fuelled by the prospect of new job creation and investment for a city that, at the time, sorely needed it.

The final nail in the coffin for the protest movement came on July 14, 1981, when police stormed the church and evicted the last remaining protesters. Widespread demolition then began. An historic neighbourhood was flattened and things would never be the same again.

Troubled birth

The new GM plant officially opened in 1985, with the first car, a 1986 Cadillac Eldorado, rolling off the line at 12.05pm on February 4 that year. Besides the E-Body Eldorado, the plant also assembled the downsized K-Body Cadillac Seville, and the controversial 1987-93 Cadillac Allante.

The assembly process for the Allante was seen as an extravagance in itself, for modified E-Body inner structures built at Detroit-Hamtramck were airlifted to Turin, Italy, where Pininfarina added the car’s bodywork. The complete shells were then flown back to Detroit on special Boeing 747 jets ready to be mated to the chassis and running gear at Hamtramck. The plant also assembled the downsized and poorly received 1986-93 Buick Riviera and 1986-92 Oldsmobile Toronado.

The late Eighties were tough years for GM. A spate of downsized, increasingly generic cars (many built at D-HAM) that alienated existing customers and failed to woo many new ones, did little to help. And the Allante, for all its promise as an “American Mercedes-Benz SL,” suffered from quality niggles, sluggish sales and was even declared by trade publication Automotive News as its “Flop of the Year” in 1987.

Furthermore, with GM’s push for advanced technology under chairman Roger Smith’s reign, poor quality control became a perceived hallmark of General Motors’ products, with final shakedown testing seemingly left to the automaker’s unwitting customers.

After GM’s restructuring in the Nineties, Detroit-Hamtramck became a bastion for full-size front-drive passenger car production, building the 1994-onwards Cadillac DeVille and DTS, as well as the 2000-06 Buick LeSabre and 2004-05 Pontiac Bonneville.

Yet, as good and dependable as they were, these cars gradually became out-of-step with buyer tastes, which increasingly leaned towards trucks and SUVs − with sales continuing on a downward slide. A decade after opening, D-HAM’s future was still far from certain.

Positive shock

In 2007 it appeared that things were looking up. GM announced its new extended range electric car, the Chevy Volt, at the 2007 North American International Auto Show in Detroit, with D-HAM selected as the plant to build it. Extensive investment and re-tooling created one of the most advanced vehicle assembly lines in the world and the first automaker-owned facility in the US to manufacture an electric vehicle. The first production Volt (a 2011 model) rolled off the line on March 31, 2010.

Since 2009, GM has invested more than $1 billion in plant upgrades, tooling and technology at D-HAM with additional products added to its assembly capacity, including the Australian market Holden Volt, as well as its European equivalent, the Opel/Vauxhall Ampera, the 2013-15 Chevy Malibu mid-size sedan, the Cadillac ELR, 2014-onwards Chevy Impala, the second generation Chevy Volt (from 2016), plus the new high-tech, multi-material, semi-autonomous capable Cadillac flagship, the CT6.

Adding CT6 production required the construction of a dedicated new body assembly facility at D-HAM − one which encompassed 138,000 sq ft and 250 robots, as well as new production techniques such as patented aluminium spot welding, aluminium laser welding, self-piercing rivets (which enable different materials to be joined together) as well as Flow Drill Screws.

In June 2017, GM CEO Mary Barra led a special “Rev Up the Resilience” town hall meeting at the Detroit-Hamtramck plant, featuring 200 women, including Facebook COO (chief operating officer) Sheryl Sandberg and a special tour which celebrated the achievements of those who work at this state-of-the-art facility. Sci-fi film and TV director J J Abrams even brought his son, Henry, along for a plant tour to experience Detroit’s revitalisation at first hand.

As this article is written, however, it seems that all that investment and optimism has been for nothing. D-HAM has fallen victim to another round of GM corporate cost cutting. When the automaker announced that D-HAM would be idled as part of its plan to free up annual adjusted cash flow of approximately $6 billion by 2020, Mary Barra said: “These actions will increase the long-term profit and cash generation potential of the company and improve resilience through the cycle.”

And so they might, but there’s also another cycle at play for Detroit and the Hamtramck assembly plant, one that seems intent on reopening old wounds. Comments such as increasing long-term profit and cash generation come as a bitter sting, particularly after taxpayers poured out billions of dollars to help the now profitable GM restructure following bankruptcy in 2009.

They also serve to remind Detroiters of the legacy of the Hamtramck plant, the neighbourhood that was destroyed to build it and the legacy of broken promises and battered dreams. It might be 2019, but for many in the city of Detroit, the closure of D-HAM makes it feel a lot more like 1981.