You might walk past this ’69 Camaro at a car show and fail to realise how special it is. When it romped past you on the way home, you’d get the message – a full-fat, 427cu in V8 in a basic Camaro Sport Coupe. Which was supposedly forbidden…

They can’t even agree what COPO stands for. Is it Central Office Purchase Order, or does that P stand for Production? Does the C stand for Corporate?

You see various versions on web forums, in books, even in the titles of businesses associated with these sought-after cars.

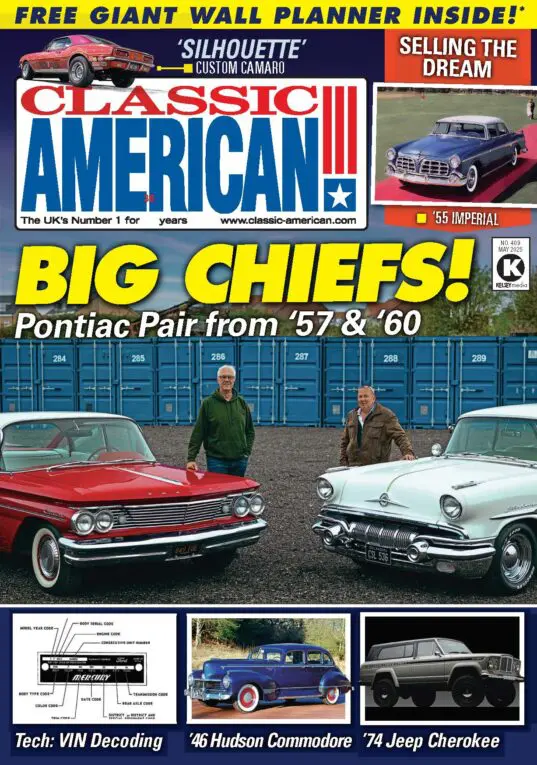

Enjoy more Classic American reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Steve Henry, owner of this spectacular rare-bird muscle machine, warned me it was impossible to talk about the history of the COPO Camaros without starting an argument, so please…go easy on us.

Here’s the gist: powerful car dealer persuades Chevrolet to allow some under-the-counter sales of Camaros with big-block V8s installed, against a corporate decision to limit the engine sizes in smaller cars. Fifty years on, they’re worshipped as the coolest of the cool, offering the Holy Trinity of desirable characteristics: great looks, stonking performance and rarity.

The detail helps too. It starts with Don Yenko, a well-connected Chevy dealer who had been offering performance parts and upgrades for customers’ cars since 1957. By the mid-Sixties, his dealership in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, was selling re-worked Corvairs called Stingers and his relationship with the top brass at Chevrolet was very good.

Vince Piggins, the man who coaxed the Z/28 into existence and did more to create a performance image at Chevrolet during the 1960s than anyone, was a key ally. Yenko knew Zora Arkus-Duntov too, and, like Piggins, the Corvette’s godfather was a racer at heart.

But even those two couldn’t get Chevrolet to launch the Camaro with the biggest and most powerful motors the division had to offer. So in 1967 Don Yenko took to converting new Camaro SS models with the Corvette’s 427-in L72 motor. He carried on in ’68 with the Yenko Super Camaros gaining more individual touches, including some pre-fitted by Chevrolet under COPO 9737.

These special orders were normally created for mundane variations on showroom cars, such as paint jobs for police fleets, or heavy-duty suspension or wipe-clean interiors for hard-working taxis. Don Yenko saw they could be used for more interesting options too, requesting 140mph speedometers and thicker sway bars for the cars he was going to convert.

All he did after that was take the next logical step and get Chevy to fit the engines too. With the connivance of just enough people at Chevrolet (step forward Mr Piggins, we presume) and encouragement from fellow dealers such as Fred Gibb, he ordered 201 examples for 1969.

Just imagine that for a minute – a single dealer, albeit a big one, ordering 201 low-spec two-door coupes with outsize V8s…that cost twice as much as a base model. Can you see your local Ford dealer persuading the bosses to sell them 200 Mustangs – or even Mondeos – with no radio, wind-up windows and drag-strip engines? Different times, no doubt.

Anyway, Don Yenko’s bold approach opened the door for other dealers to do the same, and indeed small numbers of other Chevy models (mainly Chevelles) enjoyed a bit of COPO magic. By the time 1969 came to an end, more than 1000 COPO Camaros had been sold through a number of outlets across the country.

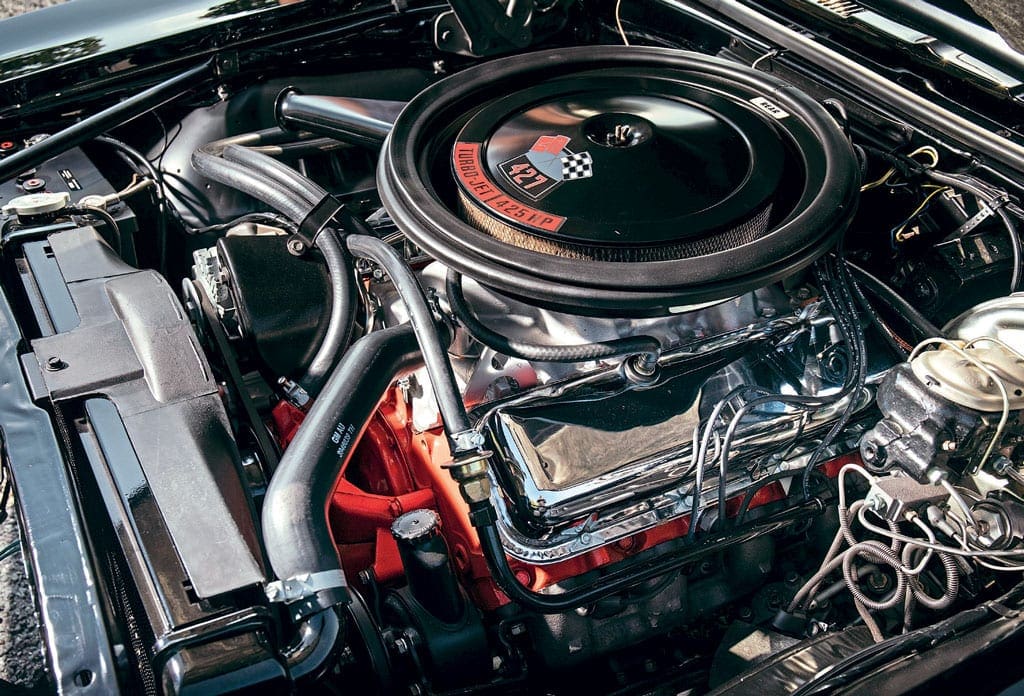

Of these, the vast majority were 9561 models, like this one. They used the all-iron 427 cu in engine making approximately 425bhp at the crank. Most were ordered with the Muncie M22 four-speed transmission and low-ratio 4.10:1 Positraction, 12-bolt rear end. But there was also the loopy 9560 model, of which just 69 escaped into the wild, with ‘wild’ being the operative word.

The engine was an all-aluminium version of the 427 big-block with a much more race-focussed specification; practically a Can-Am engine really. It was rated at 425hp, just like the iron block. And it probably did make 425bhp… at about 3800rpm. Goodness knows what it churned out at peak revs. A wink, a nod, and you were off to the drag strip, pausing only to junk the cast-iron headers and single exhaust.

The idea was simple enough – allow just enough of these potent COPO cars into the public domain and Chevy would get a reputational boost from multiple victories in the NHRA’s Stock Eliminator and Super Stock classes. But keep it on the down-low… no advertising, no brochures, no official presence in the model line-up. And it worked, after a fashion.

Yenko, Gibb, Baldwin-Motion and others had laid the groundwork for Chevy’s surprisingly serious tilt at street/strip glory, but the cost of the COPO cars was always excessive – it dwarfed the sums asked by Mopar for a Street Hemi with all the trimmings, for example.

Vince Piggins wanted a streetable version of the bonkers aluminium-engined 9560, as the one they offered was barely civilised enough to get to the strip without a trailer. But this car, when the maths was done, came out at $8581 for a manual version and $8676 for an automatic. Just the $3000 more than a ZL1 Corvette! It never got beyond a one-off.

The fate of many COPO cars was to hang about in the dealership long after they’d been ordered for stock, or for an image boost, or for the dealer principal’s son to blow people away at the local strip.

Rather like the Plymouth Superbird and Dodge Daytona, they were too costly and too extreme ever to sell in significant numbers and it’s surprising they got to a four-figure production total. And survivorship today has been trimmed by the very activity they were built for – blasting them through a succession of quarter miles will have finished off a lot of original drivelines, or indeed whole cars.

Some of them made it through intact. This Tuxedo Black example originated from Don Yenko’s home state of Pennsylvania, although it’s not a Yenko-badged car. The first known owner was a gentleman named Keven Gray, who kept the car until 1978 before passing it on to one Terry Edgar. He let it go in 1985 after which it was eventually dismantled, sitting in a garage in western Pennsylvania until it was purchased in 2012 and restored to an exceptionally high standard by a gentleman called Larry Lap.

Now it’s the property of Steve Henry, who can fill us in on the excellent tale of how it came to be his.

“I’ve had American cars since I was 18 – my first car was a ’69 Camaro, followed by many more early Camaros, Chevelles, Corvettes and El Caminos, with a few Mopars too. I was actually looking for a small-block car, a Z/28, when I heard about this.”

Steve credits – or blames – his friend Martin (‘he’s always trawling the bits of the internet other people miss out’) for locating this COPO car in Belgium.

“I assumed it would be out of my price range, but I got in touch with the vendor and we thought we should go and see it. I have to thank my wife, Bev, for allowing me to keep buying these cars… and for letting me change my mind on a daily basis!”

He didn’t change his mind about this one. The man selling the car, Tino, was an American who’d previously lived in Chicago but brought the car to Belgium. He invited Steve and Bev over to see it.

“We went over with Martin and his wife Kate. Tino and his wife made us all very welcome with a lot of food and drink and we were there for ages looking at the car and getting to know each other – something like 11am to 11pm! In the end I decided it was something I wanted and we negotiated a price.”

When Steve eventually went back in March 2018 with a covered trailer to collect the car, they made a long weekend of it and returned with probably the smartest, nicest car Steve had ever owned. Which made for a new experience, and not an altogether satisfactory one, at first.

“When we first went out in it I thought I’d never been so disappointed. The steering was vague and it tramlined all over the place. I’d pumped the Redline cross-plies up to 28psi because I thought they looked a bit soft, but then I was told that they don’t need much air in them. At 21psi it was so much better.”

These cars would clock something like 13.5 seconds for the quarter mile straight out of the box, though you have to assume that was with a better, wider set of rear tyres. Still, Steve is used to a much bigger shove in the back as he races some pretty serious machines – he’s currently building a ’67 Nova with a 615-cu-in motor and something like 815bhp, which will be a 10-second car. So is Steve one of the rare people for whom a COPO Camaro feels a bit, well… slow?

“No, it still moves pretty well! But it’s been restored to such a good standard and to totally original spec, so it’s not a car for blasting up the strip. It’s a lovely thing to be able to take out on a nice day, when you can enjoy how good it looks. It’s so clean underneath too – I don’t know if I could face cleaning it all if it got filthy, so you do tend to look at the weather before heading off to a show!”

At least it’s being driven. After an appearance on our stand at the NEC (when it must have missed our Car of the Year prize by a gnat’s whisker), Steve hid it away for the winter, though not just because of the weather – it’s too pretty to share a garage with the Nova while people are swinging spanners and using power tools.

The true COPO Camaro lasted just that one year and once the market for classic muscle got going, it rapidly became one of the most envied possessions for any collector. Hiding in a heated garage is the modern-day fate of many drag-strip specials. You don’t find original Hemi Mopars or Swiss-Cheese Pontiacs being thrashed on run-what-ya-brung days; that’s what clone cars are so good for.

But would the modern day pampering they get make the likes of Yenko and Piggins shake their heads in dismay, or smile with satisfaction? It should be the latter – they created something truly special.